Compliance

-

Blocked Property Reporting Is Not a One-Time Task

Learn why blocked property reporting is an ongoing responsibility and how continuous compliance helps prevent costly penalties.

-

The Difference Between Generic AI Tools and GRC Native AI

Discover how native AI transforms GRC with stronger governance, data privacy, and seamless integration compared to generic AI tools.

-

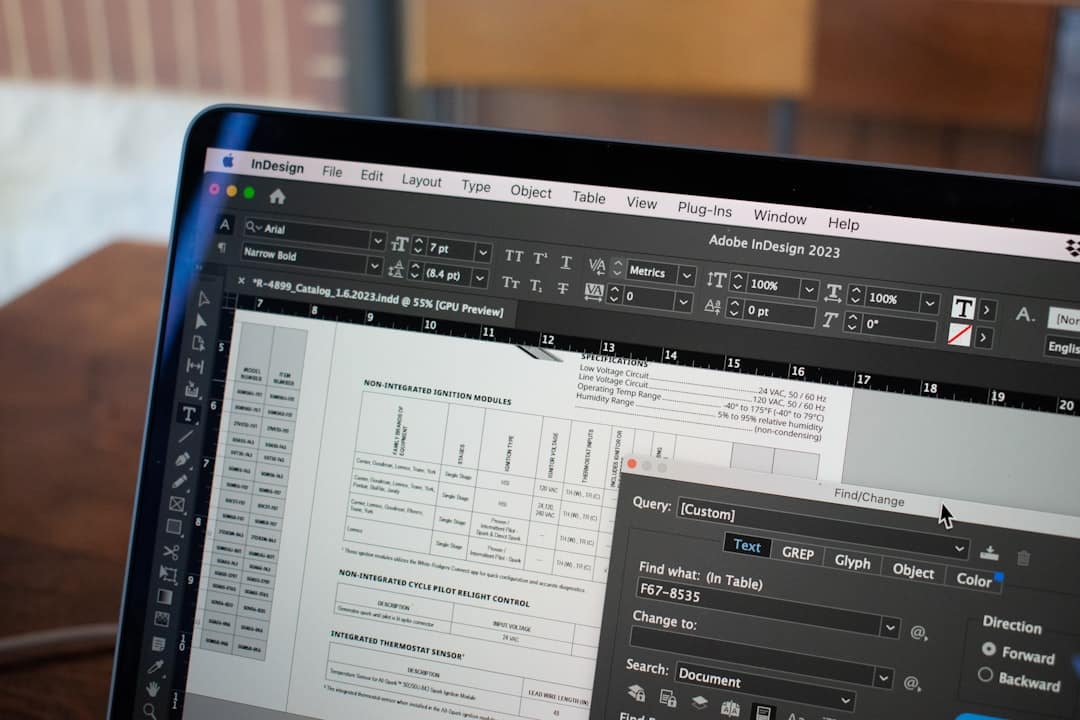

From Blank Page to Compliant Document Faster with AI

From Blank Page to Compliant Document Faster with AI– see how AI streamlines policy drafting and speeds compliance.

-

Building Your GRC Roadmap E-Book

Discover how to build a roadmap that aligns your GRC strategy with broader business goals.

-

From Blank Page to GRC Ready E-Book

Explore this guide for tips on making a confident, future-focused decision about your next GRC technology purchase.

-

Duquesne Light Company TPRM Case Study

See how Duquesne Light Co streamlined critical infrastructure compliance and third-party risk with Onspring.

-

Capture. Report. Protect. A Practical Framework for Sanctions Compliance

Strengthen your sanction compliance efforts with a practical framework for screening, reporting and audit readiness.

-

Why Spreadsheets Fail at OFAC Blocked Property Reporting

Why spreadsheets fail for your OFAC blocked property report and how centralized systems reduce compliance risk.

-

What Audit Leaders Get Wrong About Technology Adoption

Audit leadership shapes tech adoption. Learn how to reduce fear and accelerate innovation in internal audit.

-

MTM Health Policy Case Study

See how MTM Health scaled their policy management and built an integrated GRC program with Onspring.

-

The $12 Million Pixel: Why “Benign” Marketing Tech is Healthcare’s Newest Compliance Nightmare

Healthcare compliance software helps prevent pixel tracking risks, protect PHI and reduce exposure to costly lawsuits and FTC action.

-

ATC Incident Case Study

ATC achieves clear visibility, stronger accountability, and a meaningful safety impact using Onspring.